Back to Uncle Tom’s Cabin?

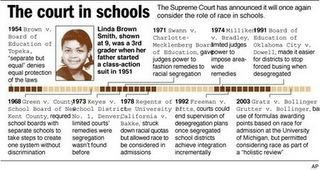

Time line shows significant decisions by the Supreme Court on the racial makeup of schools. (AP Graphic)

Jun 5, 2006

By GINA HOLLAND

WASHINGTON (AP) - The Supreme Court agreed Monday to decide whether public schools can consider skin color in student assignments, reopening the contentious issue of affirmative action in a major case that will turn on the votes of President Bush's new justices.

The announcement puts a contentious social issue on the national landscape in an election year, and could mark a new chapter for a court that famously banned racial segregation in public schools in Brown v. Board of Education.

Since then, race questions have been hugely divisive, both for the court and the public.

Three years ago, more than 5,000 people demonstrated outside as the justices considered whether public universities could select students based at least in part on race. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor broke a tie to allow it in a limited way.

The court's new interest is in public schools, far more sweeping than universities. And O'Connor is gone, replaced by conservative Justice Samuel Alito.

The justices will hear appeals from a Seattle parents group and a Kentucky mom, who argue that race restrictions improperly penalize white students.

"This is going to reach into the homes and thinking of 100 percent of students," said Doug Kmiec, a Pepperdine University law professor and former Reagan administration lawyer. "This is not quite at the level of Brown v. Board, but it will be argued in the style of that case."

Justices will look at the modern-era classroom, no longer under court desegregation orders but in some places still using remnants of those policies.

At its heart, the court will consider whether school leaders can promote racial diversity without violating the Constitution's guarantee against discrimination.

The court's announcement that it will take up the cases this fall provides the first sign of an aggressiveness by the court under new Chief Justice John Roberts. The court rejected a similar case in December when moderate O'Connor was still on the bench. The outcome will most likely turn on her successor, Alito.

Both Roberts, 51, and Alito, 56, worked as Justice Department lawyers during the Reagan administration to limit affirmative action.

Alito was asked during his Senate confirmation hearings in January about the 2003 case. Without stating his views on affirmative action, he said he taught a college seminar on civil liberties to a diverse class. "Having these people in the class with diverse backgrounds and outlooks on the issues that we were discussing made an enormous contribution to the class," he said.

The court's announcement followed six weeks of internal deliberations over whether to hear the appeals, an unusually long time.

"This is a very dramatic move. I expect it will create a big national discussion," said Gary Orfield, who heads the Harvard University Civil Rights Project and supports affirmative action.

A ruling against the schools "would be pretty devastating to suburban communities, small towns that have successfully maintained desegregation for a couple of generations," he said. "The same communities that were forced to desegregate would be forced to re-segregate."

In one of the cases, an appeals court had upheld Seattle's system, which lets students pick among high schools and then relies on tiebreakers, including race, to decide who gets into schools that have more applicants than openings. Seattle put the system on hold during the legal fight.

The Supreme Court also will also consider a policy in Kentucky, also upheld by lower courts. That case is somewhat different, because the metropolitan Louisville, Ky., school district had long been under a federal court decree to end segregation in its schools. After the decree ended, the district in 2001 began using a plan that includes race guidelines.

The Kentucky parent, Crystal Meredith, asks the court to overturn its 2003 affirmative action rulings. Her son's district still requires most schools to maintain a black enrollment of 15 percent and prevent it from going above 50 percent.

"It's a quota arrangement," said her lawyer, Ted Gordon. "The blatant segregation we once had is long gone."

The cases are Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District, 05-908, and Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 05-915.

---

Associated Press Writer Elizabeth Dunbar in Louisville, Ky., contributed to this report.

---

On the Net:

Supreme Court: http://www.supremecourtus.gov/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home