Wrongs and Rights: The 2006 Human Rights Film Festival

Going on 17 years now, the Human Rights Watch International Film Festival New York has been doing its best to make sure that audiences are not necessarily entertained, but informed. According to the festival, their raison d'etre is to "help to put a human face on threats to individual freedom and dignity, and celebrate the power of the human spirit and intellect to prevail." It other words, it could very well seem to have all the appeal for moviegoers that attending a brussell sprouts and cabbage buffet would have for children. Fortunately for audiences, the festival organizers have chosen a lineup of films notable for the most part not for their finger-waving preachiness -- though obviously that does come into play here and there -- but for their skill at telling the stories of oppressed people from around the world, stories that do actually need to be told.

The 2006 festival screened 24 films and videos from 19 countries, and it's an impressive batch overall, which is good news and bad news. Good news because the fest has been able to successfully pluck from the increasingly rich diversity of documentaries being produced these days (there are times, in fact, when the form seems the only facet of cinema still capable of astounding you). Bad news because all those submissions (500 this year) means that there are more than enough horrific episodes happening around the world to stock a dozen film fests of this kind.

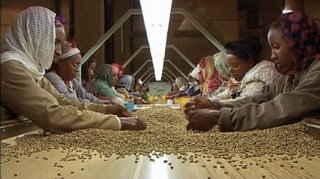

One of the fest's highlights is Nick and Marc Francis' Black Gold (****1/2), a gorgeously-shot, melancholy look at the plight of a co-operative of Ethiopian coffee growers fighting for their fair share of the exploding international coffee market (sales have gone from $30 billion to $80 billion just since 1990). The film's modest hero is Tadesse Meskela, an enthusiastic co-op member who travels the world trying to find better markets and decent prices for the 75,000 co-op members, many of whom are living on next to nothing. Given that about two-thirds of Ethiopia's export revenue comes from coffee, any drop in price can have disastrous effects, and in an international market dominated by a few multinationals like Nestle, the little farmers often have little to no bargaining power and end up selling their carefully picked crops for mere pennies a kilo.

The filmmakers contrast the Western fetishizing of coffee and espresso -- most entertainingly at the unintentionally hilarious World Barista Championship -- with the stolid, hardworking Ethiopians and the world-trotting Meskela, who knows that just getting his farmers 50 cents for a kilo would be enough to change their poverty-stricken lives forever. He also knows that if he fails, more of his farmers will be pushed to use their land to raise the highly addictive and very profitable drug chat, or even worse, be forced to rely on Western emergency aid handouts. The unspoken point here is: Wouldn't it be cheaper and more humane in the end for the West to simply pay a few cents more for coffee instead of waiting for the farmers to fall on hard times and then spending millions on last-minute aid? Black Gold shows that improving human rights can sometimes be as simple as paying more for your morning coffee.

On the other side of the planet from Ethiopia, the film The Camden 28 (**1/2) takes a similarly different take on what constitutes human rights by telling the story of the New Jersey activists who decided in 1971 to protest the Vietnam War by storming the local draft board offices and destroying their records. Director Anthony Giacchino carefully reconstructs how this band of mild-mannered Catholic laypeople and clergy was moved to radical action, and how a shocking betrayal handed them all over to the FBI at a critical moment. Almost too quiet for its own good, Giacchino's film is nevertheless a meticulous view of a quieter sort of radical and the belief that extreme protest need not involve violence.

Almost an example of how not to make a documentary on a serious topic, Milena Kavena's Total Denial ( *1/2), in which a terrifying story of near-genocide is muffled by inept filmmaking. According to the film, the military dictatorship of Burma (Myanmar) -- infamous for its police state repression -- cooperated somewhat over-enthusiastically with the company Total's desire to build an oil pipeline through a region dominated by the ethnic Karen group. The result, according to charismatic and heroic activist Ka Hsaw Wa was forced labor and murder at the gunpoint of the Burmese army. With Hsaw Wa's help, the villagers later filed suit in U.S. court against Unocal, who owned a stake in the project. While the cold-bloodedness of this project's villains (especially as shown at a Unocal stockholders' meeting in Paris) is indeed chilling, Kavena's lack of attention to detail, hagiographic treatment of the admittedly impressive Hsaw Wa, and amateurish filmmaking abilities (the editing and sound are especially rough) hardly does her subject justice.

Another poorly put-together portrait of greed, abuse and oil is Source (*1/2). Czech filmmakers Martin Mareèek & Martin Skalský, looking for a good story, head to what is in contention for being the most depressing country on the planet, Azerbaijan. They don't have to dig too deep before finding problems with the repressive government's state-run oil company, which allegedly pollutes the land at will, uses the police to forcibly annex any private property they want, and line their pockets while the country starves (although the country has an abundance of oil, supplying half the state's budget, 70 percent of Azerbaijanis live in poverty). While this setting, blithe acceptance of one's fate amid the apocalyptic post-Soviet wastes, has great potential for poignant black comedy, the filmmakers' poor sourcing -- the same handful of Azerbaijanis appear over and over again to make their claims against the government -- and inept style makes it instead the video equivalent of a numbingly dull op-ed piece.

Even though it makes no bones about having a resolutely antiwar point of view, Winter in Baghdad (***) is still a document of suffering that can't be ignored by those who disagree with it. Javier Corcuera's film starts on a stridently political note, with footage of antiwar marches and interviews with Westerners in Iraq to act as human shields, he quickly shifts gears to what is the main body of film: ordinary Iraqi citizens stuck in the crossfire. Splicing together the testimony of these unfortunate -- an old schoolteacher, a mother with a crippled boy, some children who've left school to earn a living on the street, shell-shocked hospital workers -- with some hauntingly beautiful images of a smashed and chaotic Baghdad, Corcuera has crafted an emotional archive of pain and despair. None of these Iraqis cry out for the return of Saddam, they're simply numbed from the fighting and sick of the grind of occupation. Corcuera's film is, if anything, a helpful corrective for those who want to ignore the individuals affected by war; these people are what some would call collateral damage, and they each have a story.

One of the fest's most ingenious entries is Michael Winterbottom and Mat Whitecross's The Road to Guantanamo (***), which recreates -- via news footage and reenactments -- how three British citizens (of Pakistani and Bengali descent) went to a wedding in Pakistan not long after 9/11 and ended up imprisoned in Guantanamo Bay without being charged for nearly two years. Although we've heard the stories and seen the photographs of what happened (especially early in the war) to supposed enemy combatants in U.S. hands, seeing these men terrorized by dogs, slammed into solitary and needlessly abused is another thing entirely. Although the film doesn't address opposing points of view (some parts of the mens' stories never quite add up) the "Tipton Three," as they're called, have been an antiwar rallying point in Europe for some time now, and with the release of this smartly crafted film, may soon be so in America as well.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home